An eco-friendly approach to curating your closet is more attainable than you might think, experts say

Look down any grocery store aisle, and you’re likely to spot someone studying a food package. Nutrition labels and certifications such as the USDA organic seal help us make healthier food choices for ourselves and the environment. But when it comes to clothing, consumers don’t have a lot of insight into how the garment was made and whether its manufacturers used sustainable processes to create it.

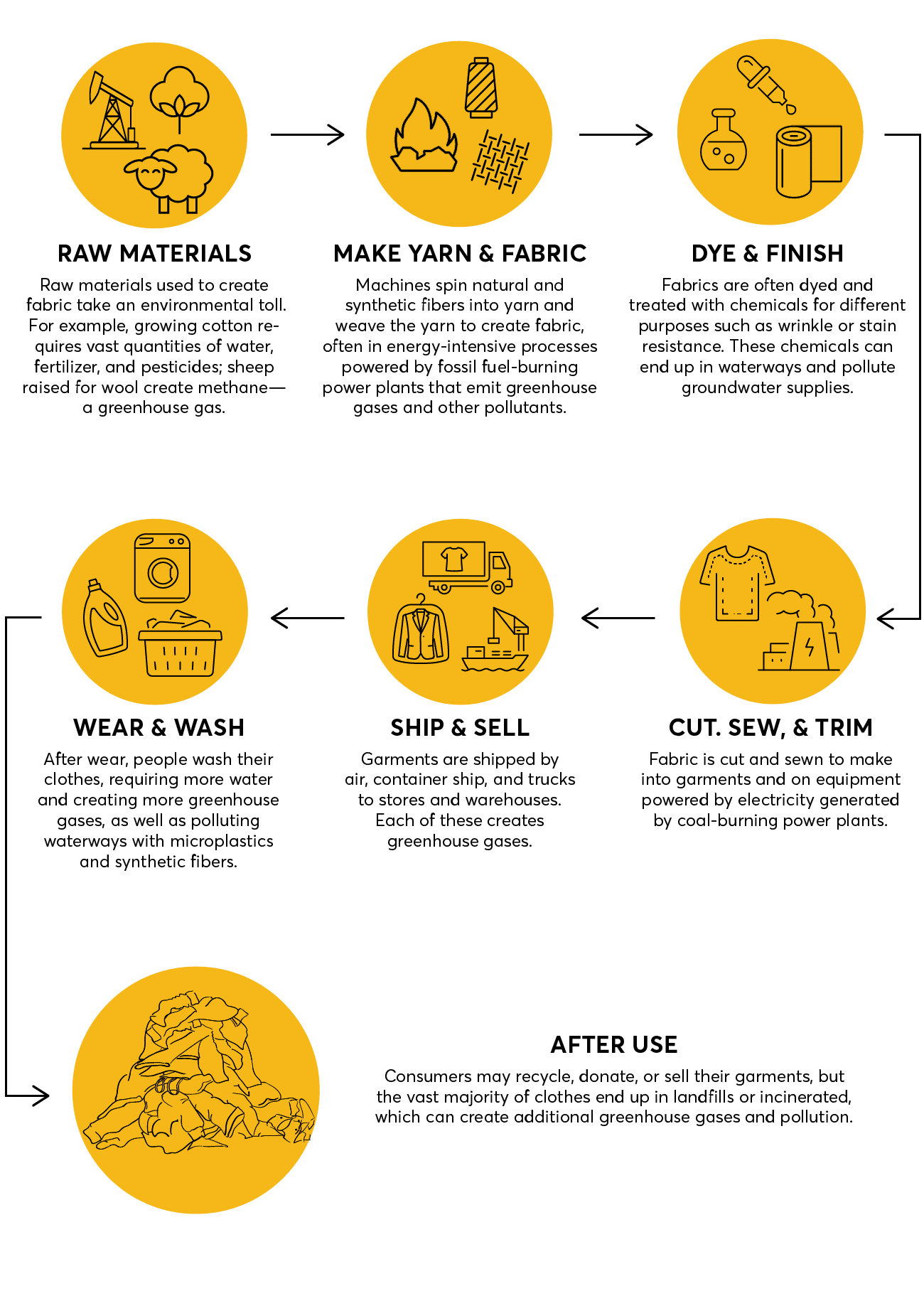

Yet clothing manufacturing and disposal takes a devastating toll on the environment. Citing data published by the UNEP and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the World Bank says that the fashion industry is responsible for 10 percent of annual global carbon emissions, and adds that “at this pace, the fashion industry’s greenhouse gas emissions will surge more than 50% by 2030.”

Making clothes is also a highly water-intensive process. For example, over its entire lifecycle—from farming to final disposal—a single pair of jeans requires as much water as a U.S. household uses in three days, according to a study by Levi Strauss & Co.

1. Buy Secondhand

“Buying vintage is your best bet when it comes to being an environmentally conscious shopper because you’re not using up additional energy to create something new—the footprint is already there,” says Linda Greer, senior global fellow at the Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs and the founder of the Clean By Design Program at the NRDC.

Even better, buying secondhand is in vogue right now. According to Shelley E. Kohan, a retail industry expert and adjunct professor at Syracuse University Whitman School of Management, “Secondhand is growing at a healthy pace over the past few years. Through November 2021 sales of secondhand merchandise are up 9.7 percent compared with 2019.”

Kohan notes that big brands are noticing the trend. “Other indications of growth are major companies expanding into the secondhand market, like Levi’s, and recently announced Lululemon.”

Levi’s SecondHand encourages customers to return used Levi’s denim items to participating stores, then cleans and lists them for purchase. Similarly, Lululemon lets shoppers in California and Texas return gently used gear, they “refresh” it, and then list it for sale at Like New Lululemon.

Shopping at Thrift Stores and Resellers

Buying at thrift stores in your area allows you to inspect and try on a garment before you purchase it—which is always a boon when shopping secondhand. But, if you need a wider selection, there are a number of fashion-focused websites where you can shop for used clothing.

The online consignment store thredUp accepts clothing as donation or sells it on behalf of customers. All garments are reviewed by thredUp’s authentication and quality experts to determine resale value, which is typically based on the estimated retail price of the item, what kind of condition it’s in, and the level of inventory in store for that size, brand, or style. For luxury items, The RealReal and Vestiaire Collective operate in much the same way, but trade in high-end designer clothing, shoes, and bags, as well as other categories such as jewelry and home goods.

Peer-to-peer platforms like Depop, Mercari, Vinted, and Poshmark allow you to buy clothing directly from individual users. While these platforms cut out the middleman, for the most part you can only return an item if it doesn’t come as described, so it’s important to be a savvy shopper. Ask questions about the garment before you buy it, such as what condition it’s in; if there are any flaws, like rips or stains; and request measurements so you can make sure it will fit.

2. Extend the Life of Your Clothes

The longer you’re able to extend the life of a garment, the better. According to a report by WRAP, a sustainability-focused charity based in the U.K., clothes typically have an average life of two years in your closet. But if you can extend that to closer to three years, it reduces its carbon, water, and waste footprint by 20 to 30 percent.

Kevin Dooley, professor of supply chain management at Arizona State University and chief scientist at The Sustainability Consortium says that clothing has two types of durability: physical and emotional.

“Physical durability is what we associate with well-made items—they’re crafted to last,” says Dooley. “Emotional durability is best measured by how often a garment is used. It’s about both the garment’s style, and whether that style is classic enough to last through evolving fashion trends, as well as how the owner of the garment feels about it.”

To increase the life of your wardrobe, shop for clothing that is both physically and emotionally durable. Sustainability expert Alden Wicker, founder of EcoCult, a website covering the sustainable fashion industry, suggests that shoppers look for high quality, well-made pieces that reflect their personal style.

“Look at the piece and ask yourself, “Would this be worth taking to the tailor to have hemmed or repaired?” If the answer is no, then it’s not worth the space in your closet,” says Wicker. “I also look at the reputation of the brand. Some brands stand by their products with a solid return policy. Others are fly-by-night “ghost brands” that sell on marketplaces like Amazon and advertise on Instagram, and won’t refund you if you’re dissatisfied with the product.”

Wicker also notes that you’re more likely to wear your clothes longer if you choose items based on your own personal style, rather than following trends. To do this, she suggests using Pinterest to save images of outfits and looks you like.

“Over time,” she says, “you start to see patterns in what you like and you get to know what colors and cuts are most flattering for you. Then, when the next trend rolls around, you can confidently say whether or not the style is for you.”

Laundering for Longer-Lasting Clothes

Another way to extend the physical durability of your clothing is to launder it carefully. Consumer Reports Test Program Leader Enrique de Paz has a few pointers:

• Wash clothes less often and/or use shorter and more gentle or delicate wash cycles using warm or even cold water.

• If your machine has a soak cycle, use it. The soak cycle lets detergent work without tossing the clothes around very much, if at all—thereby reducing wear and tear on the clothes.

• Don’t overload the machine to minimize rubbing between clothes. Use mesh bags to protect delicate fabrics from other clothes and the metal surfaces of the drum.

• Turn dark and colorful clothes inside out to minimize fading of the color. Minimize use of bleach, even the color safe types. They will all slowly take off color and even start to break down fibers, weakening the fabric.

• Use the correct amount of detergent, typically about a shot glass worth. Too much detergent can leave detergent on the clothes stiffening the fabric or you may need additional rinse cycles in the washer to remove it. More tumbling equals more wear on the fabrics. While they sell detergents that allegedly are easier on clothes, we found that these did not clean as well as “regular” detergents.

• Air drying clothes minimizes shrinkage and wear on the fabrics. If using a dryer, use low temperature and agitation settings and as with washers, don’t overload the dryer.

• Wash your clothes less. Not only does this reduce wear and tear on your clothing, but, according to Levi’s Life Cycle of Jean, washing every 10 times one of their products is worn instead of every 2 times reduces energy use, climate change impact, and water intake by up to 80 percent.

3. Sell, Donate, Swap, Rent, or Recycle Your Clothes Instead of Trashing Them

In 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated that 11.3 million tons of textile waste ended up in landfills. Methane, a greenhouse gas, is released as clothing and other waste decomposes and, according to the EPA, landfills are the third largest source of methane emissions in the U.S. Materials also decompose at different rates. For example, polyester, which made up 52 percent of global fiber production in 2018, can take decades to decompose.

So, rather than trashing your clothes, sell, donate, or recycle them.

If the clothing is in good condition, pass it along to friends and family members. Or, donate them to a church or charities such as Goodwill and The Salvation Army.

If you’d like to make some money back, consider selling them. Online consignment stores, such as thredUP and The RealReal, will sell your clothes for you and give you a cut. At The RealReal you can expect to get between 30 to 85 percent of the sale price of the item, depending on what it is and how much it costs. On thredUp, that range is 3 to 80 percent. Or, you can sell them yourself on peer-to-peer platforms such as Depop, Mercari, and Poshmark, all of which take a smaller cut—typically between 10-20 percent, depending on the platform. Right now, you can list on Facebook Marketplace for free.

And, while you probably can’t put your clothes out on the curb like your other recycling, it is possible to recycle textiles.

“Some brands, such as ADIDAS and H&M, also offer recycling programs with incentives to consumers,” says Whitehurst.

ADIDAS invites customers to ship clothes and shoes they no longer want to the company to be resold or reused. In return, customers get points in the company’s Creators Club loyalty program and discount vouchers. At H&M, you can bring any unwanted textiles to the store, hand them over at the register, and receive a thank-you coupon to use on your next H&M purchase.

You can also look for textile recycling centers in your community through Earth911 which allows you to search by zip code.

4. Shop Brands With the Right Eco-Friendly Certifications

Tracing a garment from the seed from which its fibers are made to the store where the garment is sold is a long, complicated process with many variables. That makes it difficult to determine whether it was made sustainably.

“Each stage of the production process is a way-point for sustainability,” says Greer. “From how fiber is grown and harvested to how it’s woven, dyed, finished, and finally cut and packaged. At each stage there are processes that are more sustainable—and processes that are not sustainable.”

It can be tough to trace a garment’s journey, but the more transparent a brand is about their supply chain, the more likely they are to use more sustainable processes.

One place to start is with Fashion Revolution, a fashion activist movement, and its Fashion Transparency Index, which analyses and ranks 250 of the world’s biggest fashion brands and retailers based on their public disclosure of human rights and environmental policies, practices, and impacts, in their operations and in their supply chains.

Certification by a third party that the textiles a brand is using are responsibly sourced is also a key indicator of sustainability. The Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), Standard 100 by OEKO-TEX and Made In Green by OEKO-TEX labels, and Bluesign certifications are among the most referenced among experts—each evaluates products on a set of ecological and social criteria at every stage of the supply chain. You can typically find these certifications on the garment’s hanging tag, the packaging, or in the product description online.

“Buying textiles with these certifications means that fewer toxic chemicals went into the production and finishing process,” says Greer.

Good On You is another resource consumers can turn to for help comparing brands’ impacts on people, planet, and animals. The site currently rates more than 3,500 brands based on a number of data points across more than 100 key sustainability issues, indicators, and standards systems. Good On You uses publicly available data from third-party sources such as the Fashion Transparency Index, CDP, OEKO-TEX, GOTS, Cradle to Cradle, and more, as well as reporting from the brands themselves, to generate ratings on a five-point scale. Shoppers can also download the Good On You app so that they can access the ratings from anywhere.

“Good On You isn’t perfect, but it is the platform that does the most detailed analysis of brands, from labor standards to climate impact,” Wicker says. “You can get a pretty good idea of where a brand stands by looking on Good On You. And if it isn’t listed at all? I would consider that a red flag.”

5. Advocate for Better Practices

It’s important to keep in mind that while voting with your wallet can help put pressure on fashion brands to act more sustainably, shoppers can’t save the planet alone. This issue is bigger than individual consumer choices.

Gordon Renouf, a co-founder of Good On You, notes, “There are eight consumer rights recognized by the United Nations and Consumers International. I believe that we need to recognize a ninth consumer right—the right to consume responsibly.”

According to Renouf, in order to consume responsibly, consumers need access to information about how our products are made and where they’re coming from; we need a way to trust that this information is correct; and we need to be able to easily acquire products that meet that need for responsibility, as well as other needs, such as an affordable price point.

“After spending decades in this space,” says Greer, “I’ve concluded that we need something similar to the USDA organic seal—we need a consistent yardstick that the government would create, monitor, and regulate. Brands have had the opportunity to take steps voluntarily, but it’s just not good enough.”

Dooley agrees. “Eco-certifications can indicate clothing was made in an environmentally and socially safe manner,” he says, adding that information about a garment’s durability might also help consumers make responsible purchase decisions. “Would a consumer choose or not choose to purchase a particular garment if they knew its cost per use? We also need consumer education, to make durable clothing ’cool,’ in the same way organic foods are thought of as cool.”