Article by ASU News

Earth Week at Arizona State University kicked off Monday, April 18, with the first of several events, including exciting and captivating presentations, lectures, panels, interactive installations and tours, all in recognition of the work, research and solutions being developed by the university’s researchers and global network of partners.

The week’s events are being headquartered at the university’s new $192 million ISTB7 building, with each day based around a special theme highlighting the efforts underway at ASU and beyond.

(Editor’s note: We will be adding updates to this page throughout the week. Find highlights below, including videos and links to longer stories.)

Friday, April 22

How do we foster hope?

Several experts from ASU spoke about cultivating hope in the midst of so much bad news during a Friday Earth Week session.

The panel discussion was titled, “How Do We Foster Hope in A World That Sometimes Seems Hopeless?” and was moderated by Andrew Maynard, associate dean and professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society. Here are the topics they addressed:

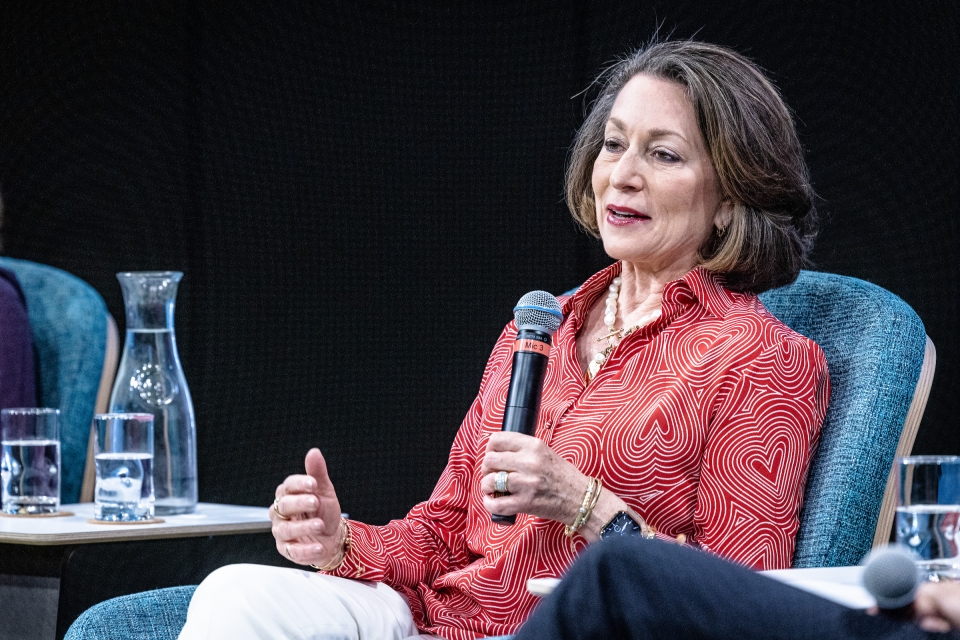

During the panel on fostering hope, Susan Goldberg — vice dean and professor of practice in the Cronkite School and former editor-in-chief of National Geographic — said journalists need to be truthful in stories about climate change but not only focus on the dire; they must give people “actionable information.” Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

On what’s needed to transform hope into action:

Nina Berman, director and professor in the School of International Letters and Cultures: “What we need the most are shared visions that lead us to action. I think right now there’s an abundance of hope in the world, but it’s the wrong kind of hope. Vladimir Putin is driven by hope for a larger Russia. There is a hope that can be very passive — ‘I trust God.’ ‘I trust the system.’ That’s why Greta Thunberg was such an event on the planet. She was a person who stood up against a whole system and modeled the type of behavior we need.”

On telling the story of climate change:

Susan Goldberg, vice dean and professor of practice in the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and former editor-in-chief of National Geographic: “You have to be honest and truthful and make people aware of the problems and the severity, but if all you do is focus on the very bad and dire, you’ll lose the audience. People will feel overwhelmed. You have to show the problems and give them actionable information.”

On using ASU’s virtual reality experience Dreamscape Learn to tell stories:

Peter Schlosser, vice president and vice provost of Global Futures at ASU: “How do we understand different value systems and cultures? I think storytelling is an important element, but it only goes to a certain point. We have to experience other value systems in their place. You cannot have everyone travel around the world all the time. My first experience with Dreamscape Learn led me to believe that this is an amazing tool to bring people to places they physically can’t go. You go into different worlds, outer space or the oceans or time travel to the Colosseum in Rome.”

‘Hope, Alarm and Climate Change’

Given the state of the planet, is it OK to have a child? With so much grim climate news, can we allow ourselves to feel optimistic? If we talk with people from around the world, can we gain new insights on how climate change is affecting their lives?

These questions and more were explored at an event Friday to celebrate the first-ever ASU Climate Narrative Prize.

The prize — created and sponsored by the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict (CSRC) and the Narrative Storytelling Initiative — originated as part of a project led by the CSRC that sought to rethink the apocalyptic framing of climate change stories and explore the potential of other narrative forms to drive social and cultural change.

Stories have the power to resonate, build empathy, influence thinking and change behavior for a chance at a better future, said Cronkite Professor of Practice Steven Beschloss, who together with Assistant Professor of language and cultures Sarah Viren taught the course “Climate Narratives, Apocalypse and Social Change,” in which students selected the top three works out of several nominated by leaders in the field including Katharine Hayhoe, Bill McKibben, Wendell Berry, Frank Sesno, Vann Newkirk and Lacy M. Johnson.

From left: ASU Assistant Professor Sarah Viren, David Montgomery, Meehan Crist, Emily Raboteau and ASU Cronkite Professor of Practice Steven Beschloss.

The winners, announced during the event, are:

- First place – Meehan Crist, writer-in-residence in biological sciences at Columbia University, for her piece “Is it OK to Have a Child?”

- Second place – David Montgomery, staff writer at The Washing Post Magazine, for his piece “The Search of Environmental Hope.”

- Third place – Emily Raboteau, professor of creative writing at the City College of New York, for her piece “This is How We Live Now.”

At the event, the winners were introduced by students from the course, who read excerpts from each of their pieces, before the authors gave their own remarks.

Crist, who shared that she was inspired to write her piece after she was asked how being pregnant affected her view of the climate crisis, said that she viewed the three winning pieces as a collection that reveal two impulses that drive writing about climate change: the impulse to bear witness, and the impulse to orient ourselves toward the future.

Montgomery, whose piece relays how he came to realize that his brother’s death may have been caused by climate change, said, “A successful piece of writing can take a subject we’ve been talking about our entire lives and make us think about it more urgently.”

Raboteau shared how she was inspired by a 2018 TED Talk given by Hayhoe to start having conversations about climate change with her friends and family, which she documented on Twitter.

In a panel discussion following the winners’ remarks, Beschloss and Viren asked them to share their thoughts on what makes an effective climate narrative.

“I think there are competing interests and needs,” Crist said. “Different effects can be made by taking different approaches. … Climate writing is an ecosystem, and any healthy ecosystem is going to have a multitude of voices.”

Thursday, April 21

The future of our oceans

Bermuda, 600 miles due east of the United States and about 900 miles north of the Caribbean, is the perfect place to base ocean studies.

That makes the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS) the perfect research partner to join the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory and give the desert-based institute an eye into the aqueous world.

“The oceans play a big role,” Peter Schlosser, vice president and vice provost of Global Futures, said at the “Ocean Futures” event Thursday morning.

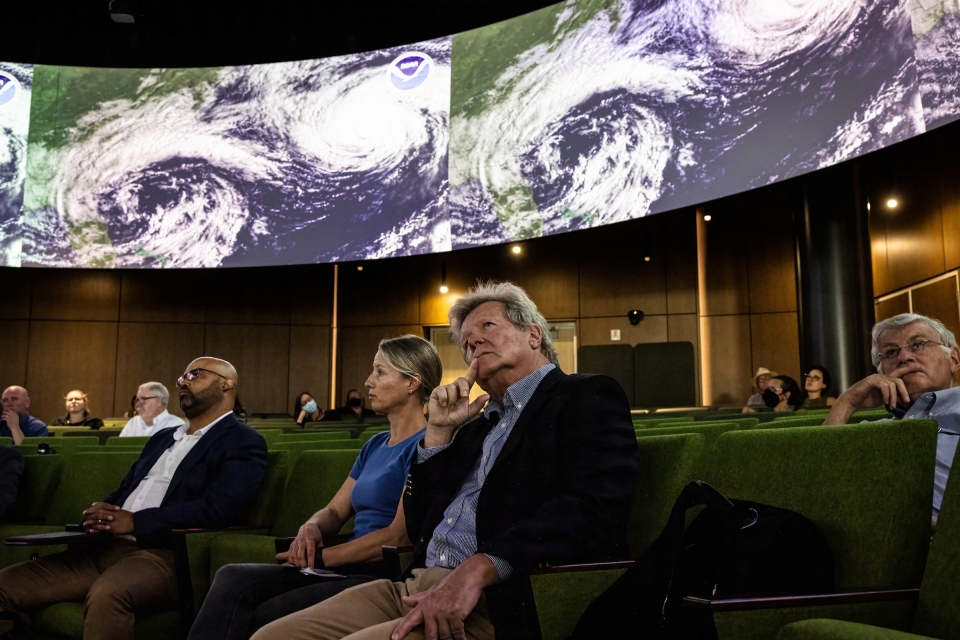

Bill Curry (front), president and CEO of the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, watches a series of videos during his presentation Thursday about the threats to oceans, including increasing carbon dioxide, acidification, warming atmosphere and loss of dissolved oxygen. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

BIOS President and CEO Bill Curry — one of the world’s leading oceanographers — gave an introduction to the institute at the event. BIOS is more than 100 years old. It started as a natural history society in 1903. By 1930 it was a deep-ocean research station. Growth came about as a result of submarines in World War I. Simply put, governments realized they had no idea what was beneath the waves and wanted to find out.

The institute carries out long-term management programs, measuring carbon dioxide levels, temperatures and dissolved oxygen levels.

Carbon is increasing in the oceans, leading to ocean acidification. It’s one of the three main threats to the seas; others include a loss of dissolved oxygen and warming waters, which lead to stronger storms.

The institute has a research vessel, the 170-foot Atlantic Explorer, which spends about 180 days each year at sea. One of its jobs is deploying Argo floats, which provide near-real-time observation of the oceans, with data uploaded every 10 days. About 4,000 of them are deployed around the globe by an international partnership. “Most of them you never get back,” Curry said.

But advanced sensors and robotics systems aren’t ready to take over from research vessels, Curry said. BIOS is currently experimenting with underwater robotic gliders.

In addition to Curry’s keynote, the session included videos on current oceans research and a panel discussion on the opportunities and needs in ensuring the health of the planet’s oceans.

From seeds to sky: Indigenous knowledge

“You can’t talk about the deep blue of the ocean or deep space without talking about the deep green of Mother Earth,” said Melissa Nelson, a professor of Indigenous sustainability in the School of Sustainability, at the beginning of the “Indigenous Ways of Knowing Water, Land and Sky” presentation.

“It’s not only about what we know, it’s about how we know it,” said Nelson, who is Anishinaabe, Cree, Métis and Norwegian (and a proud member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians).

Human blood and chlorophyll are almost identical, she said: “We are deeply connected to plants.”

She displayed a map of North America based on “foodsheds”: from the clambake nation in the Northeast to the bison nation in the Midwest to the chile pepper nation in the Southwest.

Haunani Kane, an assistant professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at ASU, talked about how native Polynesians navigated across the Pacific using the sun, stars and waves. A faint smudge on the horizon was a good sign you’d arrived at an island.The sun always rises in the east and sets in the west. A certain type of small white bird hints at land nearby, since they roost on land.

Scientists like Thor Heyerdahl theorized that ancient mariners drifted across the oceans taking advantage of prevailing currents. But Indigenous seamen navigated a voyaging canoe using traditional techniques from Hawaii to Tahiti in the 1970s, proving travel was intentional.

Katie Kamelamela, a researcher at the Biocultural Initiative of the Pacific at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, talked about Hawaiian geographical diversity. Native Hawaiians divided the land into ahupua’a: wedge-shaped land divisions that ran from the mountains to the sea. They produce different types of foods depending on the land, from high alpine forest to beaches. The Hawaii archipelago has 11 of the 13 different climate types.

“People in these areas actually reflect the personality of that climate type,” Kamelamela said.

What will the world be like 30 years from now?

Several futurists from Arizona State University spoke in a panel discussion titled “The Future in 2052: Teetering On the Edge Of Tomorrow” on Thursday afternoon. The panel was moderated by Andrew Maynard, associate dean and professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society. Here are the topics they addressed:

On the speed of change in society:

Lauren Keeler, assistant professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society who studies how futures are created through professional practice: “Things are progressing rapidly and also not progressing fast enough. We are as a species incredible at changing our environments and creating things and putting our attention on things and transforming them. But the stuff we transform and how we transform it is often not the right stuff, and we haven’t done it the right way. We’ve irreparably changed our climate. And we have not turned our attention to radically changing our Earth so we can keep living here.”

On technology:

Lindsay Smith, assistant professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society who studies migration: “If I think about migrant communities, those in the U.S. seeking asylum, and those in the camps or in Mexico or Central America hoping to migrate, if you ask them what the world should look like in 30 years, it would be that their communities are prosperous and safe, and they are able to have the livelihood they want. I don’t hear a lot of folks about bringing in technology to solve that.”

On the importance of narrative in shaping the future:

Ruth Wylie, assistant director of the Center for Science and the Imagination and an associate research professor in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College: “We ask this question all the time at the Center for Science and the Imagination. We think narrative stories, books and movies are a great way to practice the future. We need to get more futures thinking into schools. We need people helping their fourth grader with their futures homework.”

On their hopes for 2052:

Danielle Kabella, a PhD student researching the human and social dimension of science and technology in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society: “My hope for the future is that the masses have homes to live in, people have food to eat, families remain together, and what I’m trying to get at is we have these devices to imagine the future and it can be very hopeful. It’s a hopeful place to think about. But we have to have room for the nightmares, peoples’ realities that are concrete and lived in their lives.”

Wednesday, April 20

Youth and climate change

The “Power of Global Partnerships and Youth Action” panel, held Wednesday at the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory as part of Earth Week, began, appropriately enough, with a young person.

Valencia Clement, a poet and ASU doctoral candidate, read her poem “Parasites of the Planet.”

Among the lines in the poem:

“The world’s poor suffers for our satisfaction … We want to breathe free; we want to be free; we want to believe in all this country can be. Healing is the answer. Let’s honor the connection between the planets and the people by contributing to a life where our fun isn’t lethal.”

The panelists addressed the fact that less than half of the world’s national education curricula make any reference to climate change.

“What we’re hoping is climate education becomes compulsory everywhere but goes beyond learning science facts,” said Iveta Silova, professor and associate dean of global engagement at the ASU Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “How to really live with the Earth.”

Lizzie Quigley, an ASU student and universitywide sustainability chair at ASU Changemaker Central, said as part of Earth Day on Friday a student-led march will conclude at the office of ASU President Michael Crow, where they will ask that sustainability education be universal and compulsory.

Maya Soetoro-Ng, co-founder and senior adviser with the Institute for Climate and Peace and former President Barack Obama’s half-sister, speaks at the “Power of Global Partnerships and Youth Action” panel on Wednesdayat the Rob and Melani Walton Center for Planetary Health auditorium. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

That effort, said Maya Soetoro-Ng, co-founder and senior adviser for the Institute for Climate and Peace, is one reason why it’s important to treat young people as leaders in the fight to combat climate change.

“They understand the value of solutions from many different directions as we hand off the baton from sometimes behaving poorly and not being good stewards of land, space and community,” Soetoro-Ng said. “Young people are exceptional. I know that sometimes they lack some historical context, but we can help them with that. We have to trust them, know they are capable and resilient, and they are imaginative.”

Sports and sustainability

George Basile got to the point quickly.

“Topics that usually don’t come together are sustainability and sport,” Basile, a senior global futures scientist at the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Future Laboratory, said Wednesday in his role as moderator for the Earth Week panel titled “Newest Dark Horse in the Climate Game? How the Sports Industry May be a Game-Changer in Sustainable Development.”

“What is the role of sport in sustainability?” Basile asked. “What is the role of sustainability in sport?”

Over the next hours, the panelists answered those questions.

Sofi Armenakian, director of operations and sustainability for the Atlanta Hawks and State Farm Arena, said arenas and stadiums throughout the United States can be catalysts for sustainable development. She noted that State Farm arena qualifies as zero waste, meaning 90% of everything that comes into the arena for an event is either composted, recycled or re-used.

Roger McClendon, executive director of the Green Sports Alliance, said sports always has been a powerful agent of change.

“Sports kind of puts differences aside at certain points and brings everybody together in common focus,” McClendon said, pointing out that integration happened in sports before society. “Now we face a global challenge.”

Stephanie Gerretsen, postdoctoral research scholar at ASU’s Global Sport Institute, said municipalities can help meet that challenge by holding leagues and team owners accountable for sustainable development, particularly if those franchises are receiving public monies.

“Right now, municipalities aren’t asking enough,” Gerretsen said. “Out of any industry, sports have a platform and leverage to change public opinion more than any other industry, and I really think we should take advantage of that.”

Ultimately, though, it may be the athletes themselves who are the biggest players in the “climate game.” Just as Muhammad Ali and Billie Jean King brought about social change, professional athletes can influence sustainable development by holding accountable the brands they work with. Imagine, for instance, if LeBron James insisted his partner brands all work toward zero waste.

In addition, Gerretsen said, the name, image and likeness legislation that allows college athletes to profit off their names is an opportunity to promote sustainability.

“It gives student-athletes a platform to really think through what they’re passionate about and work with brands they’d really like to work with and hold them accountable,” Gerretsen said.

‘Climate Change Isn’t Fake News’

During Wednesday’s “Wicked Problem: Climate Change isn’t Fake News” panel, panelists addressed the role that both misinformation and disinformation play in tackling issues of climate change, and how the deep political division in the U.S. often stands in the way of progress.

The session was held as part of The College of Liberal Arts and Science’s Democracy and Climate Change Conference.

Nadya Bliss, executive director of the Global Security Initiative at ASU and Frank Sesno, professor and director of strategic initiatives at the George Washington University School of Media and Public Affairs, discussed the growing lack of trust in expertise and facts.

“I think one of the most interesting things that we’ve seen with the rise of social media is this erosion of trust in expertise — it’s consistent and persistent,” Bliss said. “This notion of misinformation and disinformation, and the people that are in groups that are particularly effective (at spreading) disinformation with the intent to abuse folks that are susceptible to misinformation by sharing not vetted information. … We see this with COVID, we see this with climate change and we see it with political systems.”

Although, as Sesno cited, half of U.S. voters characterize climate change as a critical threat, partisanship and corporate greed frequently hinder democracy from functioning properly to address the crisis our planet faces.

“What’s the price point of democracy? How much money do we have?” Sesno said. “We have a nonstop election cycle funded by endless, limitless amounts of money coming from vested corporate interests, conflicted interests, across the spectrum. It’s not possible for (our democracy) not to be tainted.”

‘Indigenous Considerations on Climate Change and Democracy’

Native American leaders, advocates and scholars came together to discuss the importance of including Indigenous voices in climate change discussions during the “Policy, Practice and Persistence: Indigenous Considerations on Climate Change and Democracy” panel, which was held as part of the Democracy and Climate Change Conference.

President’s Professor Brian Brayboy (seated, left) moderates a panel discussion titled “Policy, Practice and Persistence: Indigenous Considerations on Climate Change and Democracy” at the Memorial Union on Wednesday, April 20. Panelists included Clinical Professor of law Patty Ferguson-Bohnee (seated, right) and (virtually, clockwise from top left) Aulani Wilhelm, the assistant director for ocean conservation, climate and equity at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy; Haley Case-Scott, a junior policy adviser at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy; and Frank Ettawageshik, president of the Association of American Indian Affairs. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Haley Case-Scott, a junior policy adviser for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, kicked off the conversation by sharing how tribes and Indigenous peoples are disproportionately impacted by climate change.

“We are experiencing the impacts first and worst,” Case-Scott said. “In the Klamath Basin in Oregon where I grew up, the area has been experiencing extreme drought for many years. … We are also seeing warming temperatures and drought impacting the Klamath River. … Wildfires are also becoming more frequent and disastrous for people and the land. However, it is safe to say that tribes and Indigenous peoples are extremely resilient. They have managed the land sustainably from time of memorial through the passage of stories and ways that have been passed down from generation to generation.”

Other panelists echoed the sentiments expressed by Case-Scott, sharing how Native communities around the U.S. have been directly impacted by climate change, and how these communities are forced to adapt or relocate.

Although Native communities are disproportionately impacted by climate change, they are often left out of the conversation when it comes to finding solutions to these issues, said Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, the director of the Indian Legal Clinic and a professor at Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

In order to address climate change as a whole, the panelists concluded that utilizing Indigenous knowledge and philosophies, and giving Indigenous people a seat at the table, will create the lasting change needed in this critical moment.

Tuesday, April 19

The Rob and Melani Walton Center for Planetary Health

The new name of ISTB7 — the Rob and Melani Walton Center for Planetary Health — is unveiled at the building’s dedication ceremony Tuesday morning. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

In recognition of Rob and Melani Walton’s commitment and investment in sustainability solutions, ASU’s newly opened Interdisciplinary Science and Technology Building 7, located at the southwest corner of Rural Road and University Drive, was named for the Waltons during a building dedication on Tuesday.

The Rob and Melani Walton Center for Planetary Health will bridge programs to better understand the past while developing global solutions for the future so people and the planet can thrive together.

Read the full story and watch a video below about the building’s special concrete skin.

Video by Stephen Filmer/ASU Media Relations

‘Is the Constitution the Problem?’

At the opening panel of the Democracy and Climate Change Conference, hosted by The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, panelists discussed how the U.S. Constitution helps or hinders national strategies to address climate change.

Lee Drutman, a senior fellow with New America, and Richard Revesz, the AnBryce Professor of Law and dean emeritus at the New York University School of Law, discussed the political power of conservative Republicans who are skeptical of climate change. These individuals are outliers — a 2020 survey found that 55% of the U.S. population is either concerned or alarmed about global warming. However, these leaders’ positions in Congress and on the Supreme Court make passing federal environmental policies a challenge. Despite this obstacle, government entities at the state and city level have led significant policy reform, even in Republican states.

In addition to public policy, private organizations cannot be overlooked in addressing environmental challenges.

Michael P. Vandenbergh, the David Daniels Allen Distinguished Chair of Law at Vanderbilt University Law School, said that for the first time in history, household electricity emissions per capita are levelling off. This is due to the production of LED lightbulbs, a process that was driven by both government efficiency standards and private collaboration with LED lightbulb suppliers. Together, public and private entities worked together to provide affordable LED lightbulbs to consumers.

“There are challenges on each of these fronts, but each of these fronts can give us something,” Vandenbergh said. “And we can’t afford to write them off.”

The future of conservation

On Tuesday, world-renowned ethologist and activist Jane Goodall appeared virtually at ASU as part of an Earth Week discussion on the future of conservation.

“The key thing is it is not too late, but we must get together. Humanity is at the mouth of a long, dark tunnel, and right at the end of the tunnel it’s a little star. That’s hope,” she told the audience, some of whom were in person in the newly designated Rob and Melani Walton Center for Planetary Health, and others who were logged in virtually.

Jane Goodall virtually joins an ASU panel on the future of conservation during Earth Week on Tuesday. Photo by Penny Walker/ASU News

The event was a two-hour, four-part marathon session that featured a live conversation with Goodall; a talk by Peter Seligmann, chairman of the board for Conservation International; and a photo tour of the Antarctic Peninsula and the Great Lakes region by National Geographic photojournalist Keith Ladzinksi. It was followed by a panel discussion with conservationist and author Enric Sala, conservation innovator Alex Deghan and ASU Assistant Professor Haunani Kane. The event was moderated by Susan Goldberg, former editor-in-chief of National Geographic, who has a joint appointment with the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory’s College of Global Futures.

Forty percent of Earth is under active guardianship of Indigenous peoples, and that area represents 80% of the planet’s biodiversity, Seligmann said. The peoples living in these areas have the wisdom necessary to protect these places.

“These are communities that are extraordinarily wise. They have the right relationship with their place. They have the deepest regard for all species,” he said. “They understand how that place can thrive, and they have so much that we can listen and hear and learn.”

Kane discussed the overlap between traditional knowledge and Western scientific knowledge. Both use observation to better understand the world around us, she said, and both should be recognized.

“The power is in the way we tell the story and how we decide to share that story through traditional and nontraditional outlets. … Regardless of whatever obstacles are thrown in our way, we are going to succeed,” she said. “We have to succeed because this is the only place we have to call home. We don’t have any other choice but to succeed.”

Al Gore: “How Do Threats to Democracy Impact Climate Policy?”

Former Vice President Al Gore said Tuesday night that the “media ecosystem,” fossil fuel companies and their backers, and the hyperpartisan nature of today’s political scene are responsible for the “existential threat” of climate change.

Gore made his remarks in a virtual address that was part of the 2022 Democracy and Climate Change Conference, put on by Arizona State University’s The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences during Earth Week.

“The cause of the problem is using our atmosphere as an open sewer,” Gore said. “Those who want to offset the cost of their pollution by just spewing it for free into the sky that we all share and in the process is destroying humanity’s future … that has simply got to stop. It’s insane.”

Former Vice President Al Gore speaks virtually at the Democracy and Climate Change conference Tuesday at the Rob and Melani Walton Center for Planetary Health auditorium. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Monday, April 18

‘Can We Fix the Future by Fixing Energy?

Monday’s events began with a welcome by Peter Schlosser, vice president and vice provost of Global Futures at ASU, inside the university’s new $192 million ISTB7 building. Schlosser also hosted the first of several firestarter chats scheduled for this week, titled “Can We Fix the Future by Fixing Energy?”

Each member gave a different response but essentially agreed on one thing: it’s not just about energy. It’s also about economics, politics, capitalism, inequities, social and environmental justice, identity, climate change, sustainability, planning and preparedness, and human behavior. All of these elements are part of the decision-making process on how energy is created.

Andrew Maynard, associate dean and professor at the School for the Future of Innovation and Society, talks during a firestarter chat at the start of Earth Week in the auditorium of ISTB7 on Monday, April 18. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

But now, after 10,000 years of exponential growth, the stakes are higher. Where we go from here is crucial — not only to the future of energy but the future of society, the panel concluded.

“We are at a moment where really important decisions are being made about our energy systems. I’m from the fossil fuel era, and the system that’s built on wind, solar and some storage will be far more distributed, and therefore it’s open to a lot more local decision-making,” said Gary Dirks, senior director of the Global Futures Laboratory and LightWorks. “We need money to go into building a system that can at least keep us going. … When I say ‘we,’ I’m talking about all of humanity.”

‘Where’s My Stuff From and Why Does it Matter?’

From an economist’s perspective, it doesn’t matter where companies get their supplies, but from a sustainability viewpoint, supply chain transparency is hugely important.

“If you’re a food company buying a supply of wheat and it’s in an area with a threat of child labor or deforestation or where water is in short supply, that’s something you want to know because it poses a supply risk to you,” said Kevin Dooley, chief research scientist for ASU’s Sustainability Consortium and a senior sustainability scientist with ASU’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation, who spoke during an Earth Week session on Monday.

The sourcing and production of consumer goods has an enormous impact on the community. For example, palm oil is a critical commodity, used in half the products in the average grocery store, including food, laundry detergent and lip balm. The crop, grown in Malaysia and Indonesia, uses only one-ninth the land required by other vegetable oil crops. But palm oil has been linked to violations of Indigenous land rights, child labor issues, hazardous pesticides and problems with water safety.

“When I think of palm oil, an image comes to mind of monkeys and chimpanzees, and particularly orangutans, because of the impact of deforestation in Indonesia,” said Amy Scoville-Weaver, director of retail for the Sustainability Consortium. “That’s created a lot of conversation.”

Amy Scoville-Weaver, director of retail for ASU’s Sustainability Consortium, quizzes the audience at a game-oriented workshop on sustainable commodities during Earth Week. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Rob Anson, director of international sales and corporate sustainability for the Henkel Corp., which makes adhesives and consumer brands such as Dial and Snuggle, said that Henkel joined the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil in 2008.

“We have a commitment to improve how we source palm oil to make sure it’s sustainably sourced, transparent and improving the livelihoods of small farms,” he said.

Dooley said the Sustainability Consortium rarely advises a company to avoid sourcing a produce from a problematic area.

“You stay where you are, work with the supplier and the government to get the sustainable programs and systems and training in place.”

‘Don’t Look Down: Innovating our Planetary Futures with the Public’

A panel composed of scholars, educators and policy practitioners discussed the various ways their organizations engage community members through “deliberate dialogue” with stakeholders to help them solve planetary-scale issues.

Titled “Don’t Look Down: Innovating our Planetary Futures with the Public,” the panel focused on how diverse public discussion benefits science and technology, and showcased how a special unit at Arizona State University has been engaged in this practice for well over a decade.

ASU’s Expert and Citizen Assessment of Science and Technology (ECAST) formed in 2010 for the sole reason of cultivating public discourse by giving them a voice in science and technology. Some of the past topics where they’ve engaged with the public include space, climate change, human genome editing and driverless cars.

The process, panelists agreed, is equally as important as the outcome.

“We must find a way to hear from more diverse people,” said Carrie McDougall, senior education program manager for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “To me, it’s not an option … it’s a moral imperative.

MechanicalTree to help fight climate change

ASU Professor Klaus Lackner (center) talks about the carbon capture technology known as the MechanicalTree during Earth Week. Reyad Fezzani (left), vice chairman of Carbon Collect, and Associate Professor Matt Green join him. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

The first commercial-scale “MechanicalTree” is being installed at ASU, on a test pad just north of the Biodesign C building. The tree is based on the research of ASU engineering Professor Klaus Lackner, a founder of the idea of direct air capture for the removal of carbon dioxide from Earth’s atmosphere.

Lackner has been working with Carbon Collect Ltd., from Dublin, which has taken Lackner’s pioneering ideas and will make commercially available devices for the removal of carbon dioxide from the air.

The team talked about the device and technology during a panel titled “Scaling Innovation: How the MechanicalTree Exemplifies Innovation at Scale.” Attendees then got a tour of the device after the panel.

When completed and operational, the MechanicalTree at ASU will rise to a height of 33 feet (10 meters) to collect carbon from ambient air. Once loaded with carbon, it will retract into a canister that is 9 feet (2.7 meters) tall, where it gives up the carbon drawn from the air. When operated continually, is expected to remove up to 200 pounds (90 kg) of carbon per day.

The MechanicalTree prototype is partially extended for a demonstration during Earth Week on Monday, April 18, outside of Biodesign C on ASU’s Tempe campus. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News